How did the Game Change? Is it Still Changing?

A deep dive into the change of shot distribution through time in the NBA, and the reasons behind it.

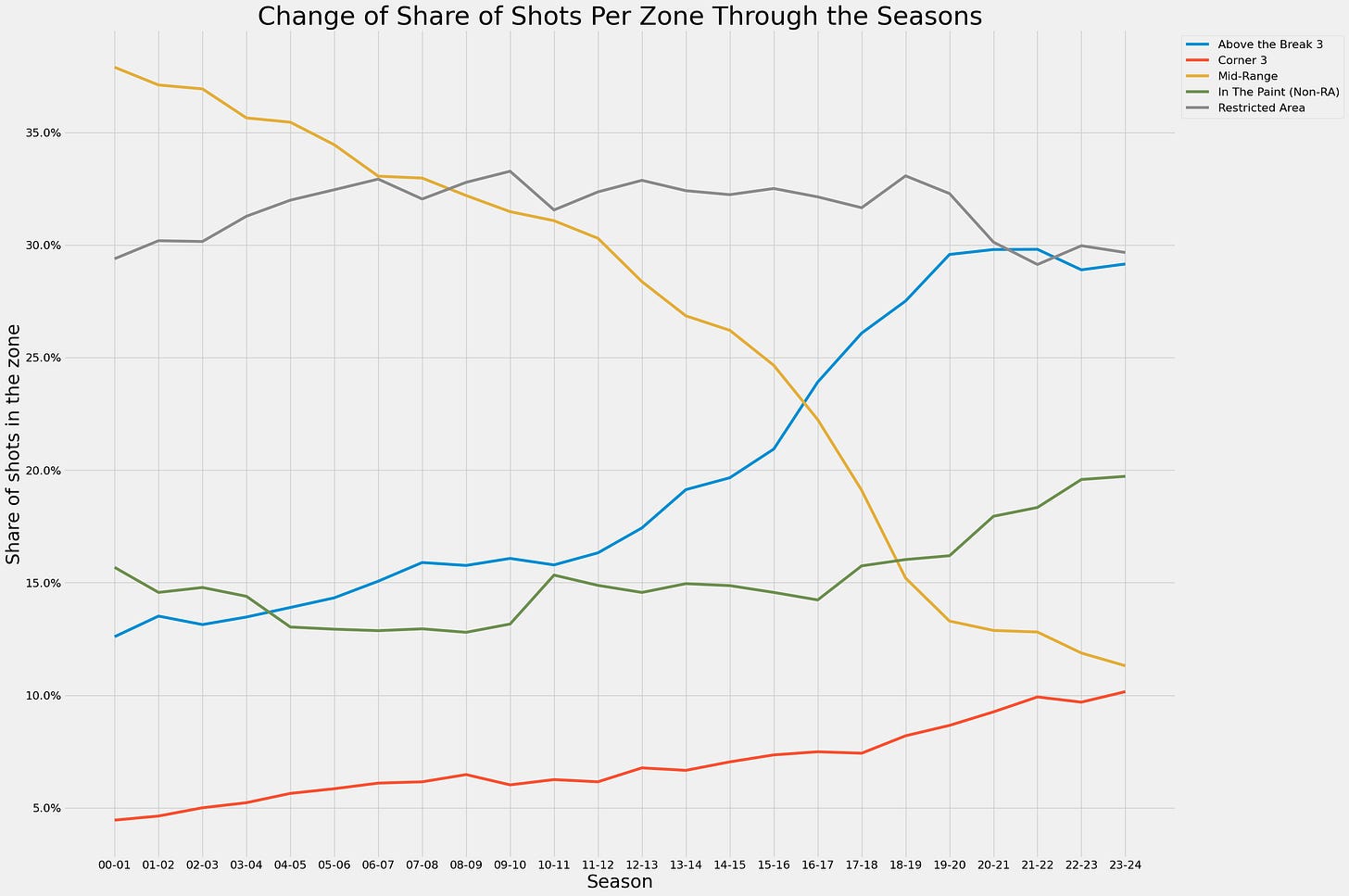

Every basketball fan/enthusiast has certainly come across some variation of this chart/image, most often published by Kirk Goldsberry. I first saw his charts back in 2018-ish and that got me involved with the world of basketball analytics. I’ve noticed he posts a variation of this chart quite often, at least once a season (no really, 19-20, 21-22, 21-22 again, and 22-23). They always blow up and have a shitload of engagement, reach, and other social media metrics so I kind of do understand why he is posting this constantly.

What I want to try to do is dive in as to why and how the game has changed the way it did. I’m not the first one doing this deep dive, and I think some people have done it a lot better than me (links in the end!), but this topic is dear to me and I want to tackle it here using the play-by-play and shot data that we have at our disposal.

The Basics

The basics of the change are simple, the teams started to figure out the well-known “knowledge” that 3 > 2, so they began to funnel all those mid-range shots toward the 3-point line. But I think a better way to grasp that would be to put it out on the court.

Each bin on the chart is represented with a color spanning from white to brownish color where white represents the lower value, of 0.7 points per shot or less, while brown color is around 1.3 or more - I capped the values at 0.7 at 1.3 → restricted area certainly has some bins over 1.3 for example.

Restricted area and corners are the places to be and shoot from, while above-the-break 3-pointers are next in order their shade of brown is generally close to 1.1 points per shot which is a lot better than the bleak white color that spans across the entire mid-range and outside of the paint. Even those elbows that were the targets of many curl and floppy actions are just average at best.

If we switch a flip in our mind and observe colors as the frequency of shots - we would then pretty much get a modern-day distribution of shots on the court and even the chart at the right side from the start of the text. So this chart alone already gives hints as to why basketball has changed.

How did the game change?

Now that we understand the basics and the foundation of why the game has changed, we can go into the tidbits of how it changed. We can examine the details of shot data to try and find the reasons behind the disappearance of baseline and elbow shots (spoiler alert - shot data alone won’t be enough).

Let’s start by observing which player positions changed their distribution the most.

The thing that bothers people the most nowadays is that everyone plays the same style of basketball, only shooting threes and diving into the paint. Well, the right-hand charts would confirm that thinking, I would disagree with it though, because, on a deeper level of basketball analysis, there is a huge difference in how, for example, Sixers and Nuggets set up Embiid/Jokić in their favorite situations.

Because of that thinking - people also often mention that basketball got boring. I agree with the statement, in a way. That is because there is no more random shit happening during the game. If Nenê Hilario played in today’s basketball you wouldn’t see him randomly taking up a baseline jumper as he did back in 2003-04 when playing for Denver. When things get efficient, they get boring.

Big Men Increased the Range - How the Big Men position got “Brook Lopezed”

Centers and forwards have seen the biggest increase in total increase of 3-point rate (20% more 3-pointers today than in 2003-04) - and that’s where the overall influx of 3-pointers is most seen.

Rasheed Wallace, Rashard Lewis, Al Harrington, Channing Frye, and Ryan Anderson have all started paving the way towards spacing the floor back in the late 2000s and early 2010s just for Kevin Love and especially Brook Lopez to change the way centers play the game completely. Lopez was an amazing traditional big man, playing in the low post, scoring through a variety of post moves, and crashing the boards - all that earned him an all-star spot on the Nets. Then one year Lopez just decided to start shooting 3-pointers and making them at an extremely efficient rate.

And exactly those types of players (Brook, Myles Turner, Chet Holmgren, Jaren Jackson Jr., etc...) are one of the main reasons for achieving great spacing.

No Posting Up

By moving the centers outside of the 3-point line, you automatically have a lot fewer post-ups, which were frankly mostly unnecessary and forced poor shots. We don’t have to (and can’t actually) go back to 2003-04 to check the difference between post-ups through the numbers. But we can notice that huge difference even when we compare the current number of post-ups with the 2015-16 season - the first available year of post-up data from nba.com.

Back then, the median number of post-up possessions per game stood at 7.6, nowadays the maximum is 8.6. But the post-ups in today’s game have become a super efficient setup with 10 teams performing 1 or more points per possession. In 2015-16 the most efficient team was the Thunder, with exactly 1 PPP. The New York Knicks in 2015-16 with Carmelo Anthony and Kristaps Porzingis were putting up only 0.89 points per post-up, and this season’s Cavs are last with 0.88 PPP.

Fast forward to the present time and Porzingis has become a 1.27 PPP post-up player and is performing better in post-ups than even Jokić and Embiid (and everyone in the league basically), while in the 15-16 season he earned only 0.82 PPP. Teams have improved in the way they play the game, and in the way they pick their spots to attack opponents.

When you space the floor and stop clogging the lane with post-ups, you’re allowing your guards to drive more easily and make defenses vulnerable.

Guards Simply Expanded the Plays

Guards were and still (mostly) are the biggest catalysts of NBA offenses, and because of that, their most common shot locations changed the least in these 20 years. However those elbow jumpers are now spilled into above-the-break 3-pointers, and those long mid-range baseline jumpers are corner 3-pointers. Players nowadays don’t pump fake their defender who is closing out, and then step into the 2-point area, but step aside for a 3-pointer.

Peja Stojaković was one of the best shooters of his era who would certainly reach even higher levels had he played in modern basketball.

Coming off a handoff in this situation, Peja continued to dribble to the FT line and pull up for a middy. In today’s game, Peja would have pulled up and probably drained a 3-pointer. Here are full highlights in case you want to check them out.

Peja was quite advanced for his time, as he was one of the few who shot a higher volume of 3-pointers. If we look at his entire career he has averaged 2.2 3-point makes on 5.5 3-point attempts per game - good for 40.1%. He indeed was ahead of his time. Imagine plugging him in today’s Kings’ team…

Here is another great example of Rip Hamilton, one of the best mid-range (almost exclusively mid-range) shooters.

As with Peja, Rip also stops his motion around the elbow and curls toward the hoop for a shot. There are also plays where he runs off-screen, and stops and pops for the long 2 along the baseline!

The same ideas were present in all other plays as well. Flare screens for shooters used to end up in a long 2-pointer, and the isolation game ended up in a 20-foot-long mid-range instead of getting closer. That was the standard operating procedure back then. Constant sets included 2 big men who weren’t interested in shooting further than 10 feet and players dancing around them trying to get open usually inside the 3-point line.

Today’s basketball has almost all these plays, but the only difference is that players have to perform them faster, run more (since they’ll end up outside of the 3-point arc), and be disciplined about it. These little details have become standard and “unwritten” rules in the game of basketball.

The Game has Actually Stopped Changing - in a way

The 2019-20 season when COVID-19 interrupted the NBA season (and the entire world) seems like it just happened, but that was 4 years ago already (damn). And since then, the changing of the game has stagnated significantly.

Looking at this chart you can instantly notice that the rise of ATB 3-pointers and the decline of mid-range shots has plateaued.

But actually, the game is still changing, maybe not in a way Kirk hints with his posts (and the first chart of this text). Players are taking a lot more “short” and “mid” mid-range shots (yeah it sounds confusing, but I don’t know how to lay it out differently).

That’s driven by the way the teams play their defense. They want to take away both 3-pointers and restricted area by employing drop defense. So attackers have to adjust.

We can notice a positive change in the efficiency of both mid-range shots and paint shots (outside of the RA). A change of 4% is quite significant for the paint area. Players such as Luka Dončić, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, and Nikola Jokić have gotten extremely skillful at navigating around the paint and using their bodies to get the best possible shots.

The slight increase in the 3-12 feet distance range bumps the share of shots for the “Inside The Paint” zone. And being dangerous in that area has enabled the Nuggets (and some other teams) to be a mismatch nightmare for the entire league.

P.S - The restricted area shots are excluded from the chart showing efficiencies because the average efficiency in there has improved from 63% to 66%, which is a significant jump, but it skews the chart because of the values constantly dancing around 60% (the RA FG% has jumped from 60% to 66% when looking back at 2017-18, and it preceded the jumps in other zones).

The Midrange isn’t Dead - It’s Reserved For the Best

So yeah we’ve been talking about the decline of mid-range throughout the entire post, now it’s time to defend it. In a manner of the well-known proclamation:

“mid-range is dead, long live the mid-range”

The mid-range and further parts of the paint are reserved for the best of the best. Most of the unassisted shots come exactly from those zones on the court.

Despite guards pulling up a lot more for above-the-break 3-pointers, we still have a large number of role players who are mostly knocking down catch&shoot 3-pointers, thus the unassisted rate for above-the-break 3s isn’t rising. The same goes for the restricted area - despite breakthroughs in the geometry of offensive teams and neverending spacing, there is still a greater number of cutters and rim runners that are pulling down those numbers.

The only two areas that haven’t seen a decline in the unassisted rate throughout the years are mid-range and In-The-Paint. This season we have a relatively big spike in the overall assist rate, with 63% (3% more than in the past 5 years, for example - that’s a huge outlier actually) of FGM ending up as assists, so that’s why we have a decline in unassisted share across all zones, but the general trend shows how more than 50% of both mid-range and “in-the-paint but outside of the restricted area” shots are unassisted!

Closing Remarks

I’ve covered a lot of topics throughout this text, so I’ll try to summarize it all for those who might have skimmed through the post - I don’t blame you for that.

Spacing - baseline jumpers turned into corner 3s

Centers and forwards started to expand their range, and thus teams were able to space out the floor and use every inch of it

Sharpshooters curling and “floppying” to a 3-point line

Shot creators who used to shake their opponents only to take a minor step inside the 3-point arc have gotten smarter and started stepping back or aside before shooting. Catch&Shoot players have simply extended their movements to the outside of the arc unlike in the 2000s.

Efficient basketball = boring basketball

In general, this is true, the teams play very similarly today. But I have a hard time accepting that someone would find Jokić, Dončić, Wemby, Shai, Kyrie, or Embiid boring. All of them have a vastly different bag of tricks for reaching the goal of getting buckets.

Stars still take mid-range shots

The rise of “short” mid-range is pretty apparent and it’s countering the most common drop defense that teams deploy. Players are getting more skilled in finishing through floaters, hooks, close-range fadeaways, and other great imaginative shots.

What Lies in the Future?

Rule change.

I’m a huge fan of the removal of defensive 3-seconds. That would enable A LOT better defensive zone schemes where players wouldn’t have to think constantly about 2.9ing. The offensive rating across the league is through the roof despite referees raising the bar on foul criteria (the free throw rate is the lowest in the modern NBA). The pace has also started to slow down, and it’s now at the levels of the 2017-18 season, and the overall number of 3-point attempts has also started to plateau, as shown.

But the teams, and players, just got better. Some of the moves that are nowadays common and not impressive at all have been a complete unknown 20 years ago. The offenses need a new challenge, the easiest way to achieve it is with a rule change. Only then can we move the game even more forward.

Reading material:

My old blog post on this topic. It contains very similar concepts, I just tidied up some of the charts and ideas, and maybe even my writing has improved since then.

The Midrange Theory by Seth Partnow - great great book. The title of the book is also the central chapter of it. It was published in November of 2021, and I’d say that I’m influenced by it in my general basketball thinking. I think I’ve managed to hit some of the ideas Seth talked about in my old blog post (first dot)!

Tweet by Todd Whitehead talking about this topic but with much better and more detailed charts and data thanks to Synergy Sports annotations

Detailed post by Todd about this same topic. This is a great post from December 2021 but I’ve read it only recently (at the time he posted the tweet above!) Highly recommend it!