Estimating the Quality of a Passer - Part 1

Skimming through the possible adjustments and additions to passer valuation

An assist is credited to the player tossing the last pass leading directly to a made field goal, but only if the player scoring the goal demonstrates an immediate reaction toward the basket after receiving the pass. Note also that an inbound pass can be credited as an assist if it leads directly to a field goal.

This is the official definition of an assist coming from the NBA’s video rule book, and the definition makes total sense, but I still “highlighted” (or rather bolded) an interesting part. "instant reaction to the basket" is something that can manifest itself in countless different ways on the floor.

One assist might come from a play where a point guard snakes through the traffic while being double or triple-teamed and notices a cutting big man storming toward the hoop and throwing him an alley-oop pass where he needs to jump and slam the ball. The other assist might be a play where a spot-up shooter passes the ball to a star player who then ISOs up and knocks a turnaround fadeaway contested jump shot. The result is always 1 AST.

A valid question one might ask themselves now is: “Are All Assists Equal?”

The numbers, metrics, and research on the quality of shots and shot-making have been a focus point in the past 10 years in the world of basketball analytics. That makes sense since shot-making is the most important part of the game and its development directed how media and fans evaluate players and teams. Other parts of the basketball game are a bit behind in the world of analytics, so it’s not surprising that it might be hard to gauge the quality of a passer and his assists simply on the raw count of assists.

We’ll try to dive into this segment of the game in this post, and hopefully find something interesting that might paint us a better picture of how good of a passer and shot creator a player is. In my opinion, there are two paths toward those metrics.

The traditional way of getting a better glimpse of that is to consider turnovers and calculate the AST/TO ratio - but that might include ball-handling and other dead-ball turnovers so we might not get a full picture of it. This can be easily corrected by parsing the play-by-play data to find only bad pass turnovers. This already scratches the surface of analytics, and by using those two extra sources we could get spatial awareness of the quality of assists.

The modern way is to use the power of tracking cameras, thus tracking data. We can easily check the amount of potential assists a player generates by visiting the NBA’s tracking stats about passing. Using that data point, we can get a more detailed view of shot creation and passing. But we’ll touch on that sometime later.

The Traditional Way

Let’s first check the traditional way and expand it with the change that I mentioned above.

Bad Pass Turnovers

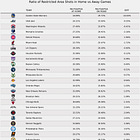

I’ve included 3 extra columns that usually aren’t present when summarizing the traditional stats on any major stat websites (NBA, BBRef, …). It’s just a simple filtering of turnovers so that we only have and see the bad pass turnovers on the right side of the table and AST/BP_TOV ratio for every player.

These new numbers/metrics can properly give real credit to a player who might seem like a turnover-prone passer → such as Domantas Sabonis or Giannis Antetokounmpo. They have some of the worst assist ratios out of these 20 players, but that’s mainly because they have a lot of dead ball turnovers - that might sound familiar to you as I wrote about that two weeks ago in my Chart Dump post:

In reality, Sabonis and Giannis often hit their player on the mark and rarely turn the ball over by passing it into opponents’ hands, especially since both players operate a lot through the handoffs. 10% of all Kings’ shot attempts fall on handoff actions, which is by far the biggest number in the league (biggest in absolute values as well - 11.6 possessions per game). If you’re wondering what team is the best in handoff plays’ efficiency - that would be the Milwaukee Bucks.

The other thing we can look for in this table is to find the absolute lowest AST/BP_TOV ratio. For the top 20 assisters this year that would be Darius Garland. Garland fits perfectly as a point guard from our play in the introduction where he snakes around the court and tosses a perfect lob to Allen or Mobley for example, so how accurate is it for us to say that he is a bad passer because he has a low AST/BP_TOV ratio? Not quite accurate - and that’s why I would concur that this stat should be used simply to correct some of the negative outliers (such as Sabonis and Giannis), not to berate players because of the low ratio - for that, we need more context.

Assessing the Difficulty of Converting Assists

To try and portray Garland in a better light, I’ll resort to one of my old analyses on my “old” website (I mean, it’s still active, but I don’t post anything there or have any custom stats or tools - for now) but I went too aggressively with rhetoric that there are real and fake assists - come to think of it, given the initial definition I think NBA assists were always given in a same way but the shot data got more sophisticated.

However, the chart from that post could be useful with some reworking. I manually tried to divide/classify shot types into “easy” and “tough” shots that were scored after an assist. Tough shots are all shots that came from drives, pull-ups, step-backs, and turnaround/fadeaway shots. Easy shots are alley-oops, running shots (those should actually be fast breaks), cuts, jump shots, and normal layups/dunks/hooks…

When we divide shots into those two categories and take a look at those same 20 players, Garland is the best among those players in total share of assists that resulted in easy shots - 85% of those actually which is an insane number. Young, Dončić, and Cade are also in the upper half in the share of “easy” shots.

Sabonis and Jokić often operate in the handoff and thus have a lot of assists that end up in “tough” or semi-self-created shots. Murray, KCP, MPJ, etc… go for a pull-up or drives after handoffs.

If we combine the previous two metrics into a single chart, we get the following scatter chart.

The ideal passer would have a good assist-to-bad pass-turnover ratio, while also having a big ratio of easy shots but no player is ideal. This gives us a good perspective that it’s tough to balance dishing a ball on a plate and being safe when passing the ball.

There also isn’t a volume dimension in this chart, and it’s not the same to compare Haliburton and Garland as Hali has 5 more assists per game than him.

I think I’ll stop here for now, I realized that there is a lot more I could go into with this topic. Some more numbers and metrics can be pulled out in a “traditional” way by playing with PBP and shot data, and I plan to start with that segment in the next post.

Until then, have a good time!